Rude Hand Gestures of the World by Romana Lefevre is a

photographic guide to the many ways of using hand gestures to offend people in

different parts of the world. The book’s photography is by Daniel Castro, and

published by Chronicle Books of San Francisco.

A hand gesture is arguably the most effective form of

expression, whether you’re defaming a friend’s mother or telling a perfect

stranger to get lost. Learn how to go beyond just flipping the bird with this

illustrated guide to rude hand gestures all around the world, from asking for

sex in the Middle East to calling someone crazy in Italy. Detailed photographs

of hand models and subtle tips for proper usage make Rude Hand Gestures of the

World the perfect companion for globe-trotters looking to offend.

Chin Flick

Meaning: Get lost

Used in: Belgium, France, Northern Italy, Tunisia

In France, this gesture is known as la barbe, or “the

beard", the idea being that the gesturer is flashing his masculinity in

much the same way that a buck will brandish his horns or a cock his comb.

Simply brush the hand under the chin in a forward flicking motion. While not as

aggressive as flashing one’s actual genitalia, this gesture is legal and

remains effective as a mildly insulting brush-off.

Note: In Italy, this gesture simply means “No.”

Idiota

Meaning: Are you an idiot?

Used in: Brazil

A South American gesture indicating stupidity, this requires

improv skills and an actorly flair. To perform, put your fist to your forehead

while making a comical overbite. The gesture is most effective when accented

with multiple grunts. When executed correctly, you will be rewarded with

appreciative laughs, though not, perhaps, from your subject.

Moutza

Meaning: To hell with you!/I rub **** in your face!/I'm going

to violate your sister!

Used in: Greece, Africa, Pakistan

The Moutza is among the most complex of hand gestures, as

elaborate and ancient as a Japanese tea ceremony. Perhaps the oldest offensive

hand signal still in use, the Moutza originated in ancient Byzantium, where it

was the custom for criminals to be chained to a donkey and displayed on the

street. There, local townsfolk might add to their humiliation by rubbing dirt,

feces, and ashes ("moutzos" in medieval Greek) into their faces.

Now that the advent of modern sewage systems and anti-

smoking laws means that these materials are no longer readily available, the

Moutza is a symbolic stand-in. In Greece, it is often accompanied by commands

including par’ta (“take these”) or órse (“there you go”). Over the years, the

versatile Moutza has acquired more connotations, including a sexual one, in

which the five extended fingers suggest the five sexual acts the gesturer would

like to perform with the subject’s willing sister.

Five fathers

Meaning: You have five fathers, i.e., your mother is a whore

Used in: Arab countries, Caribbean

If you are looking to get yourself deported from Saudi

Arabia – possibly amid a riot – you can do no better than the Five Fathers

gesture. The most inflammatory hand gesture in the Arab world, this sign

accuses the subject’s mother of having so many suitors that paternity is

impossible to determine. To execute, point your left index finger at your right

hand, while pursing all fingers of the right hand together. The insult is

extreme and almost certain to provoke violence.

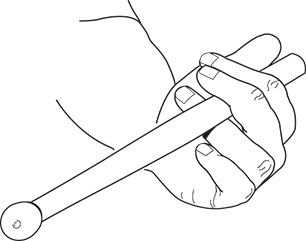

Pepper mill

Meaning: crazy

Used in: Southern Italy

In southern Italy, craziness is indicated by this gesture,

in which one mimics the grinding of a pepper mill. The implication is that the

subject’s addled brain is whirring as fast as the mill's blades.

Corna

Meaning: Your wife is unfaithful

Used in: The Baltics, Brazil, Colombia, Italy, Portugal,

Spain

Informing a friend that his wife has been unfaithful is an

unhappy and delicate task. Fortunately, in many countries, it is simple to do:

one simply gives him the Corna. A very old sign, the Corna dates back at least

2,500 years and represents a bull’s horns (bulls were commonly castrated to

make them calmer).

Be warned that while the gesture is used throughout the

world, its meaning varies greatly from country to country.Should you be on the

receiving end of the gesture, before you cast out your wife, remember that your

pal may simply be saying she is a fan of American college football or heavy

metal bands.

Note: In Saudi Arabia, Syria, and Lebanon, one makes a

similar gesture with an identical meaning by fanning out the fingers and

placing the hands by the ears to mimic a stag.

Write-off

Meaning: I am ignoring you

Used in: Greece

The literal translation of st’arxidia mou, the phrase that

accompanies this gesture, is “I write it on my testicles.” And while there may

well be people who, out of a strange psychological compulsion or simply

boredom, actually write on their testicles, here the threat is simply

metaphorical and tells the subject you’re ignoring him. One needn’t possess

testicles to use the gesture, which is employed by men and women alike.

Cutis

Meaning: Screw you and your whole family

Used in: India, Pakistan

Should you find yourself in India or Pakistan, wishing to

insult not just your host but your host’s entire family, look no further than

the Cutis gesture. Its origins are unknown, but its effect is swift and severe.

Simply make a fist then flick the thumb off the front teeth while exclaiming

"cutta!" (“Screw you!”). In short order, you will find himself

ejected from the premises, your mission to offend thoroughly accomplished.

Tacaño

Meaning: You're stingy

Used in: Mexico, South America

Just as the heart is associated with love, so, in many Latin

American countries, is the elbow with stinginess. In Mexico the two are so

closely linked that a miser is described as "muy codo" (very elbow),

the idea being that he rarely straightens it to pay the check. If your compadre

makes a habit of failing to pick up the check, you may wish to correct his

behaviour with this sharp gesture. For extra emphasis, bang your elbow on the

table.

Note: In Austria and Germany the same gesture means “You’re

an idiot,” suggesting that the elbow is where the subject keeps his brain.

Fishy smell

Meaning: I find you untrustworthy

Used in: Southern Italy

In business, it is important to let your associates know you

can’t be taken advantage of. This gesture informs them you are on to their

attempts to deceive. To perform, move your nose side to side with the index and

middle finger. The movement suggests that something stinks, and you are trying

to rid yourself of the odor.